Harvest Moon and The Comfort of The Incomplete

A reflection on my interview with Cassandra Wilson for Wine Spectator and how the incomplete gives us complete pleasure but at what expense?

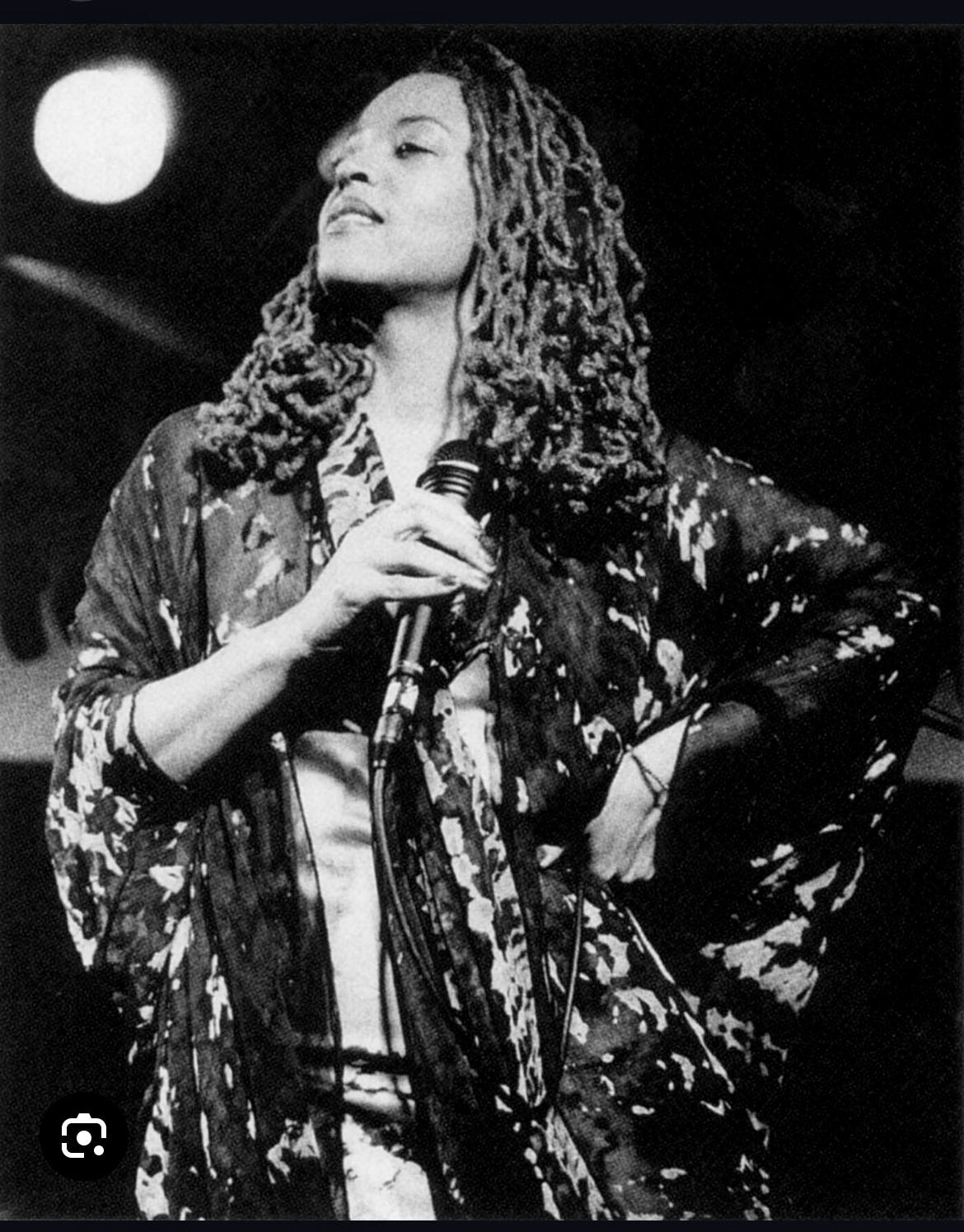

Years ago, I interviewed Cassandra Wilson about her passion for wine in a profile I wrote for Wine Spectator. If you don’t know who Cassandra Wilson is, please Google “Cassandra Wilson Harvest Moon” and feel free to thank me in the comments. Her voice is a gift to hearing.

I remember being nervous about interviewing Cassandra Wilson because her sound was so haunting, her voice, like it crawled out of a time before human cargo ships, a time when you could put your ear against the soil and hear the earth’s very heart beat.

Cassandra talked about loving French whites, wines from the Loire Valley–Sancerre and Vouvray. She described her recording sessions as food and wine tastings. While recording in her native Mississippi, she served white wines with gumbo, jambalaya, étouffée, catfish and West African–style tamales. Sometimes she served Veuve Clicquot which she absolutely loved.

What did not make it into the story was a very awkward pause during the interview when I brought up Nina Simone. Cassandra Wilson’s voice reminded me of Nina Simone, and when I mentioned that, it was clear she didn’t like the reference. I remember very clearly what she said, “Nina Simone is a song interpreter.”

The quote never left me, and over time, I began to understand what she meant. Nina Simone’s voice was its own dialect, an outburst, a visceral sound connecting what was and what still is. In this sound was a constant longing, an aching for a complete life.

It’s a sound I recognize and identify with growing up in the church. The black church is that symbol of a relentless longing and a relentless pursuit of a complete life, a life where we’re not holding up signs and marching and posting prayer emojis on Instagram posts while staring at the latest black face forced out of its body. A complete life where we’re not exhausting precious air in discussions about basic dignity. If the black womb could speak, it would speak Nina Simone.

As I explore these sounds for a larger literary work, I consider the wines I have been attracting these days. If you’ve been reading my work for a while, you’ve heard me say or write that the wines we attract are often a reflection of where we are in our lives at that time.

When I interviewed Cassandra Wilson, I was leaving California Zinfandel and drinking more southern French wines–Minervois, Côtes du Rhône, Côtes-du-Rhône Villages, Lirac, Gigondas, Vacqueyras, etc. I craved dark, rich, earthy wines.

In sommelier school, I wanted so much to have a Châteauneuf-du-Pape moment. I had read about the tiny region, the 13 grapes associated with the appellation laws, memorized the 13 grapes–grenache, syrah, mourvèdre, cinsault, etc. Tasting Châteauneuf-du-Pape felt like the completion of an era of study when I associated tasting the wines of these revered regions with achievement and status. In the end, the Châteauneuf-du-Pape bottles I tasted reminded me of dirty rain water.

Over the years, my palate has lightened up, and it’s been so obscenely hot in Miami, I’ve been craving light reds, rosés, and sparkling wine. Low alcohol, high intrigue. A couple weeks ago, I bought a bottle of piquette–a style of wine that I read existed hundreds of years ago. The simplest description I could find was “an ancient beverage made by repurposing grape pomace, skins, and seeds after traditional winemaking.”

The wine I bought, The Piquette Project Rougette in California, is made from “red grape must, reconstituted with juice to activate fermentation, a second fermentation happening in the bottle.”

The result was tricky for me to process. It just didn’t taste like wine. So I got a second bottle. Was the wine sound? When I was in somm school, this is among the first questions you ask about the wine you’re tasting. Honestly, it was hard to answer the question. My gut said “No.” But my mind understood that the mission wasn’t soundness but sustainability–to take what remains of the wine after it is processed and create a beverage. It was the very definition of conscious winemaking which is important to me.

But, on the other hand, the notes reminded me of sparkling wine that is left overnight in an open bottle or the bar I worked mornings at in Manhattan back in the days. I couldn’t shake those notes of old rags used to wipe down bar counters and sticky floors. The wine tasted incomplete. Many wine professionals would have described it as “flawed,” but there it was stuck in my memory worthy of inner-dialogue.

I felt similarly about a bottle I bought for my birthday last month. It was a South African cinsault. Because there’s no real South African wine culture in South Florida, especially South African wines in the natural wine genre, whenever possible, I support them.

But this wine called Mother Rock Presents 2020 Brutal Red was just that, brutal. It was more noisy than “funky” (a word, over popularized in the natural wine space). What some might describe as a “sour cherry” note was strained and overpowering acidity. It tasted incomplete. And given how overpriced it was, a huge disappointment.

But I understand the value of the conversation it presents: If an incomplete wine brings complete pleasure to consumers, then does it matter?

While the Brutal was not a piquette, I was still curious about the ancient wine and wanted to try other producers and learn more about its history. The graph below popped up in various versions after my search:

“Derived from the French word for “prick” or “prickle,” which describes the drink’s slight fizz, piquette dates to ancient Greek and Roman times, when it was known as lora. Considered a meager, cheap-to-produce drink made from the scraps of winemaking, it was given to slaves and field workers.”

My eyes kept trying to move past the word, “slaves” but couldn’t. The sentence was incomplete. It was filled with ghosts.

As someone who has researched and written about the relationship between the slave trade and wine history, what I know for sure is history is humanity. It is the story of humans–their condition and how that condition–past and present, informs that society’s socioeconomic identity.

But history’s incompleteness keeps us safe. It coddles our pleasure. In Sedale McCall’s post entitled “Harsh History: Is There Virginia Wine Without Slavery?” on SommTV.com, he writes:

The story of Virginian settlers and Jefferson almost always ignored the labor critical to Virginia wine at that time. For example, in 1773, Thomas Jefferson gave Italian viticulturist Filippo Mazzei 2,000 acres in order to plant European vines requiring enslaved African-American labor.

What’s most present in this compelling article is the longing for a complete narrative about wine and not just slave labor but the acknowledgement of the black winemakers in Virginia’s history.

It is about a two hour flight from Virginia to Mississippi, a state with its own jagged history. I can only imagine what it must have been like in those jam sessions with Cassandra Wilson–the smell of West African-style tamales, jambalaya, and étouffée mixed with her beguiling voice. What would I bring? That Moscatel de Alexandria from northwestern Spain or the one from Chile, sangiovese from Umbria, that chillable red from Uruguay. It would be a vibe, I’m sure. A total, complete vibe.