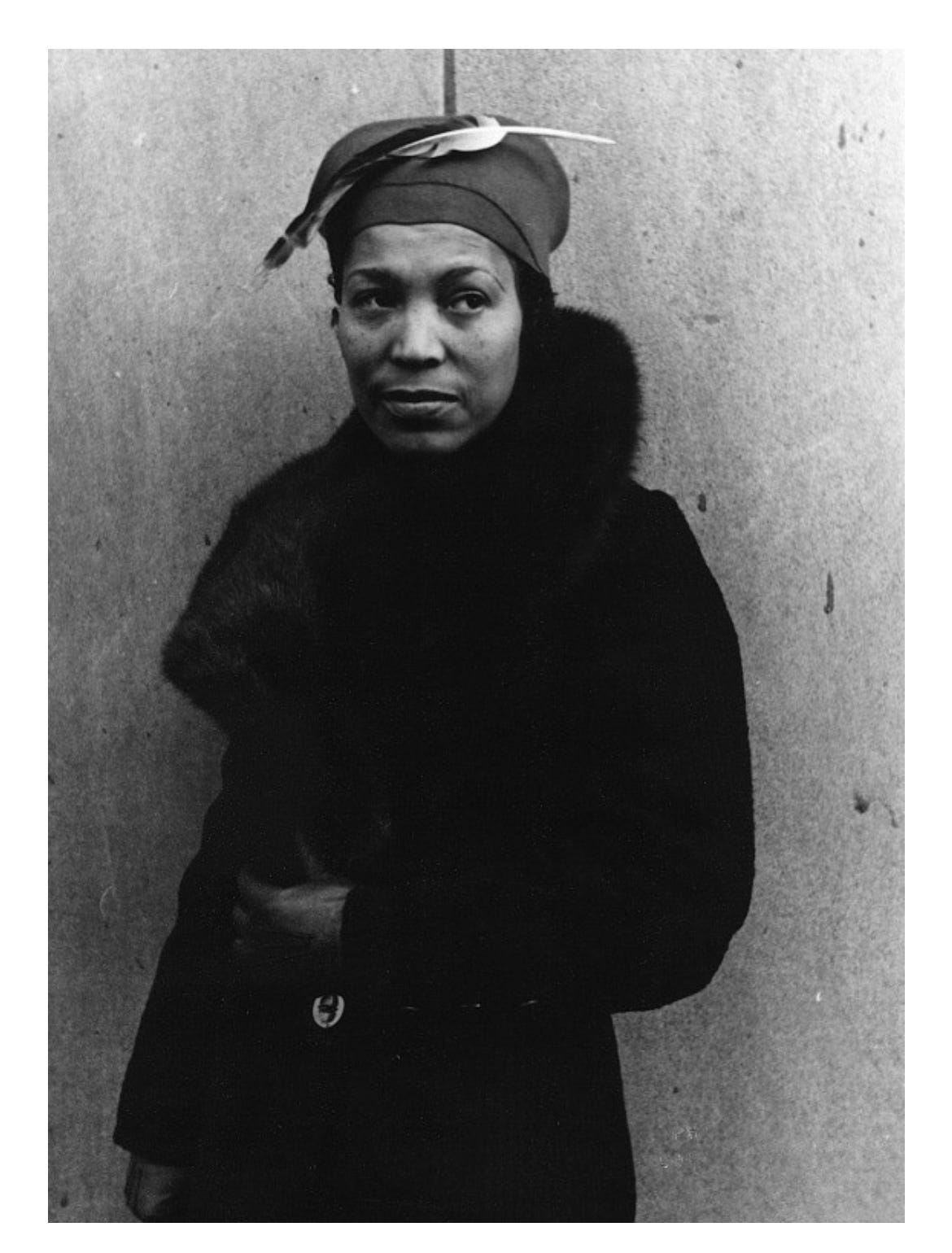

Smells like Zora’s Spirit

Reflecting on the mystical midwife of the black southern story, the terroir of the tortured state, and the agonizing beauty that remains

I had suffered a brutal breakup. The ghosting kind. The one where one minute, we’re in each other’s skin, bone-to-bone. The next minute, silence.

It was a time when cell phones were just becoming an integral part of our daily lives. Brooklyn was still Brooklyn, and I could see the Twin Towers from the roof of the brownstone where I lived.

My mentor and friend, Karen, had given me a copy of Zora Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes Were Watching God.” I belonged to a literary community that adored Hurston's work, but at the time, all I knew about her was that she was from Florida.

So in the cave of my despair, at the bottom of that winding staircase, where Broward Boy, and I had fucked and feasted, I read and wept.

I read the entire book on that spring Sunday afternoon. But I remember being embarrassed, even ashamed that I didn’t “feel” the book the way so many of the writers I respected, felt it.

Before Brooklyn Boy, I dated a music editor who read 3 or 4 books a month. When he was in reading mode, I wasn’t allowed to come over. He regularly reminded me of my underdeveloped literary palate. “Maybe you don’t grasp abstract concepts,” he said because I didn’t feel the film “Clockwork Orange” or was it “Eyes Wide Shut.” While we were together, he read Ayn Rand’s “Atlas Shrugged,” and “The Fountainhead.” I went to India and discovered Mahatma Ghandi’s “The Story of My Experiments with Truth.”

I had become self-conscious about my reading palate in the same way I was self-conscious about my wine palate. Red wines that were tannic with high acid just didn’t resonate. I cringed at sangiovese, but found comfort in johannisberg riesling.

But what did that mean? I didn’t fully belong to myself, and so I had no real measure of understanding what I liked. When so much of the self is pasteurized through processes of being seen, being chosen, and being accepted, what remains are vestiges of the truer, lesser known self.

I wanted to impress the old white men in tasting rooms and at publishing houses, so I spoke perfectly, I shared my tasting notes. While on the surface these notes were a rebellion against the banal wine descriptions that were pervasive back in the late 90s and early 2000s when I was on the come up, there were still efforts to impress, to be seen, to be chosen. Sweet, fried plantain to describe muscat, Jamaican black cake to describe Amarone (I was obsessed with 1997 Bertani Amarone).

In that performance, what sustained me were my roots. I was the daughter of proud Jamaican immigrants who grew up in a vibrant, intense immigrant city where hope tasted like harrowing trips over a ravenous sea. Hope tasted like rice and beans and overnight shifts and tambourines and botanicas. What I knew is what moved me, and I held on to that.

I was barely holding on when I met Zora Neale Hurston many years later in graduate school. This time, I was in a different bone-to-bone state:

“Mama died at sundown and changed the world,” Hurston writes about losing her mother at 13 years old.

On the first day of summer, my mother died at dawn and also changed the world. Two months after her death, I ran into the arms of academia the way most people run to church. Hurston’s spirit was there to greet me. Along with Morrison, hooks, my paternal grandmother–Coralee Iyvadney Vaughn and other literary ghosts.

It was the season when Donald Trump was not yet president though there were whispers. The New Yorkers hadn’t taken over Miami. Housing in Miami was still moderately affordable. Local wine folk were talking about “natural wine.” And I traveled to Umbria with a group of professors, doctoral students, and a young woman who was becoming a nun to visit the tomb of Santa Clara.

With my mother gone along with the routine of watching her kneeling at her bedside, hands clasped tightly praying for me, I was lost. I can see her now, a blue paisley headscarf tied around her head, a jar of holy oil on her nightstand next to a giant Bible, its burgundy, leather cover peeling like skin. Going to Umbria to visit Santa Clara was somehow connecting me to my mama.

Hurston must have felt alone after that sundown that changed the world. She grew up in a home where religion and education were priorities. Her father was a preacher and was described as “domineering.” My parents were also preachers, and my father, too, had his domineering moments. Hurston was a mama’s girl. Her mama encouraged her to "jump at de sun." Mine, too.

After Hurston’s father remarried, she was sent to a school in Jacksonville where she found comfort “nowhere.” Then there is an eight year period of her life that is unaccounted for. In this absence, I find the most tension and connection to her story.

The years that follow this mysterious break, first at Howard University, then in Harlem, and at Barnard College as the intellectually fetishized negro girl, are a result of her mother’s death and all we do not know–the lovers and the prayers, the wandering and the longing, the dying daily. The rising again. and again. This is when the poet is born. This is when the storyteller is riched in fire and becomes.

In spring 1940, Hurston arrived in Beaufort, South Carolina, to study religious trances. For more than ten years, the anthropologist and Harlem Renaissance writer– alone, a woman, a black woman, braved the monstrous ways of the south to record the stories of her people. She was a story collector in a time so unfathomable, every effort has been made to amputate these chapters from the body of American history.

In this way, Zora Neale Hurston was a mystical midwife, collecting dangerously, in the rural south– researching, writing, and recording the ways of a people in a constant state of imminent death. The way their bodies moved when they caught the spirit or The Holy Ghost, the sounds they made.

It was the time of Jim Crow. It was a time of black bodies swinging where the cold wind blows. There’s footage of Hurston playing drums during a church service where people are playing tambourines, guitars, and cymbals.

They’re clapping hands, skins slick with sweat.

They’re clapping hands, skins slick with sweat.

They’re clapping hands, skins slick with sweat.

This was part of Hurston’s research, and it betrayed the classic science of anthropology–white coats and clipboards standing in “objectivity” or more accurately, in the case of white men of that time, documenting black and brown stories, in judgement. Unqualified, at best, to comprehend such sounds as these white men, their history was a blood river of scalping, smothering, silencing the indigenous, the natural, the true.

Hurston was interested in all aspects of Black folk. She was researching herself as much as she was researching and documenting the people around her. This curiosity formed when she was just a girl:

“There were no discreet nuances of life on Joe Clark's porch.

There was open kindnesses, anger, hate, love, envy and its kinfolks, but all emotions were naked, and nakedly arrived at.”

This reminds of me of the Haitian elders in Miami sitting under coconut and mango trees in the evening, a small radio nearby discussing issues about their homeland, Cuban and Jamaican men slamming dominoes on tables, market women with thick arms and even thicker dreams laughing and gossiping and boasting and commiserating about their Americanized children.

When Hurston arrived at the Alabama home of Cudjo Lewis, one of the last known surviving Africans of the Clotilda, reportedly one of the last American slave ships,

Hurston called him by his African name, Oluale Kossola, to greet the elder who shared poignant recollections of his capture.

Hurston’s unmarked years stick with me–a humming sound, an undiscovered bottle or region. They led her to Oluale Kossola. This was more than a curiosity of wanting to understand the relationship between African and African American traditions. This was a calling to know the terrior of the tortured state, its nuances, its smells, the aftertaste that lingers from one generation to the next.

Over several months, Hurston was with Lewis in Africatown, the village he co-founded after the Civil War with other West Africans. She seemed to connect with him like a found niece, offering this elder who was in his late 80s tributes of food, driving him around. There was trust, and it was sweetly divine.

In choosing to record things as they were, Black folks as they were, which I’ve heard described as part of Hurston’s “iconography,” it was also part of her exclusion, her otherness.

Her death was unromantic. That iconography would reach its heights after she gave up her ghost. But what remains was the masterful survivor who made up stories to navigate the southern men she encountered while researching and collecting narratives:

“I took occasion to impress the job with the fact that I was also a fugitive from justice-- bootlegging. They were hot behind me in Jacksonville, and they wanted me in Miami.”

Jesus H this is beautiful.